The spectrum dimension provides the foundational sound of the timbre explorer which is further shaped by the other three dimensions. Perceptually, the sound is more hollow for lower spectrum values, but becomes more and more full as the spectrum value increases from left to right. From a technical standpoint, the spectrum dimension controls the base wave-shape of the sound. For the Timbre Explorer, the wave shape starts off as a sine shaped wave on the lower (left) end, then to a square shape, and finally a sawtooth shape at the higher (right) end. At the extreme ends of the spectrum range are special case waveforms which don't follow this smooth waveshape progression. The reason for this specific progression of waveshapes is best illustrated by the wave's Fourier Transform, which shows the wave in the frequency domain. Frequency domain graphs are commonly referred to as the spectrum, but for this project, the distinction should be made between the raw spectrum dictated by this dimension and the final spectrum shown in the black graph.

Frequency domain graphs show the frequency content of the waveshape, typically in the form of a series of peaks. Each "peak" on the graph represents a frequency that's present in the sound, with low frequencies to the left and high frequencies to the right. Notice how the peaks are evenly spaced for most of these spectrums. This means the frequency of each peak is an integer-multiple of a fundamental frequency, which is the first (left-most) peak in the spectrum. These kinds of integer multiple peaks are referred to as harmonics of the fundamental frequency. A sine wave-shape is characterized by having none of these harmonics, with its spectrum only being a single peak. For this reason, sine waves are commonly referred to as "pure tones". As we morph from a sine to a square shape, you can see the harmonics gradually enter the spectrum. At a certain point, the shape becomes a full square wave but immediately begins to change into a sawtooth shape. When this starts to happen, you'll see that new harmonics will start to sprout between the harmonics of the square wave. These new harmonics are the even-numbered harmonics of the fundamental frequency: twice the fundamental, four times, six times, etc. The square wave harmonics that grew before are the odd-numbered harmonics: thrice the fundamental, five times, seven times, etc. Square waves are often described as hollow compared to sawtooth waves, which are described as having a fuller sound. It's fitting that this is our perception since square waves only have odd harmonics, leaving hollow spaces where the even harmonics should be. In comparison, the sawtooth waveshape features the full range of both odd and even harmonics.

In instruments, this base spectrum is determined by the physics of how the instrument vibrates the air. Most wind and string instruments closely match the characteristic of sawtooths, boasting both odd and even harmonics. An exception is the clarinet which is closer to the square wave, with greatly diminished even harmonics As previously mentioned, there are special inharmonic waveforms at the top and bottom of the spectrum range. At the top of the range, the sawtooth wave is slightly detuned from the fundamental. This kind of inharmonic behavior is linked to percussive string instruments like guitars or pianos. At the bottom of the range are 4 special harmonic distributions meant to mimic tonal percussive instruments: the vibraphone, marimba, glockenspiel, and timpani. Can you recognize which is which? You may need to set the frequency range to match that of the actual instrument.

While this was the system I designed to encompass a wide range of sounds along a smooth 1-dimensional parameter, the reality is that the raw spectrum can be anything. Noise signals, for example, are not characterized by peaks at all, but instead by a evenly distributed wall of frequency content. The fourier transform is a widely used tool to analyze signals. If you'd like to learn more I'd encourage you to find some kind of tool or program capable of this kind of analysis (for example Audacity or Sonic Visualiser) and seeing what different kinds of sounds look like in the frequency domain.

The brightness dimension is the first of out shaping dimensions, acting on the waveshape produced by the spectrum dimension. Perceptually, sounds with a low brightness are....dull. As you increase the brightness from left to right, you'll hear the sound become more and more bright, up to a point where it becomes too bright and sounds tinny. From a technical standpoint, the brightness module is a frequency filter. In the middle of the brightness range is a neutral setting: the filter is off, and no effect is actually applied Below this neutral range, the filter is a low-pass filter, which blocks high-frequencies and allows low-frequencies to "pass". The result is a timbre that sounds more muddled. Above the neutral range, the filter is a high-pass filter, which blocks low-frequencies and allow high-frequencies to pass. Frequency filters act by decreasing or increasing the amplitude of certain frequencies, but unlikely simply making the whole sound louder or quieter, not all frequencies are affected in the same way.

The behavior of the brightness filter is characterized by the frequency response function graph, which shows how the filter responds to different frequencies. Like the Fourier transform of the spectrum, low frequencies are on the left and high frequencies are on the right. For the low pass case, in the lower end of the brightness range, the frequency response has a greater amplitude on the left (for low-frequencies) and lesser amplitude on the right (for high-frequencies). The opposite is true for the high pass case. In the neutral setting, we see that the response is that same across all frequencies, as we would expect. As the brightness value is moved farther away from neutral, the cutoff frequency of the filter scales correspondingly. This cutoff frequency represents a target frequency that the filter is designed to start attenuating for all values greater or lower than it (depending on the filter type). The brightness filter's effect on the spectrum can be visualized by overlaying the brightness graph on top of the raw spectrum, with the resultant spectrum seen in the black final spectrum graph.

Physically, brightness can be affected by many things. Things like the material of the instrument or its construction can have an effect. Most instruments are designed to have specific resonances which amplify some frequencies, making others comparaitvely quieter. Such resonances are constrained by size, which is why most instruments will not have particuarly strong frequency components that are too high or too low. There also may be external factors that affect brightness. Brass mutes, for example, are designed to be high pass filters. When sounds pass through solid objects, like walls or doors, they become low-passed. And finally, sounds played through speakers are affected by the construction of the speaker. Cheap speakers often lack good low end response and thus are effectively high pass filters. In reality filters are all around us and have uses that extend far beyond music.

To truly capture the sounds of real instruments, filters much more complicated than a simple low pass or a high pass are needed. AS previously mentioned, the construction of instruments themselves is a filter. Such filters amplify specific frequencies, rather than broadly blocking a wide range. It would be difficult to account for all these kinds of nuances in a smooth 1-dimensional progression, not to mention computationally expensive.

The spectrogram begins to introduce time variance to the timbre. Perceptually, the best way to describe the effect is through onomatopoeias. As in the brightness dimension, we have a neutral setting in the middle of the articulation range. At low articualtion values, the sound is an increasingly pronounced "BWAA" sound. At high articulation values, the sound becomes more of a "NYUU" sound. The way these sounds are made are once again thorugh the use of a filter. However, unlike the brightness filter, the articulation's filter has a cut off frequency that changes over time.

The articulation graph is perhaps the most complicated graph to explain. This is because spectrograms are actually three-dimensional graphs, shown on a two-dimensional space. The third dimension is intensity, typically denoted by the intensity of the graph color. In the case of the articulation graph, there are only 2 color settings: off (white) and on (green). Spectrograms show how the frequency of sounds change over time. One way to think of it is that each vertical slice of the spectrogram is its own spectrum at that given timestamp. So for low articulation values, the sound starts with its lowest frequencies active, and as time progresses, the higher frequencies of the sound are brought in. This can also be visualized in the final spectrum, where harmonics fill in from left to right (low to high). This is most easily seen for extreme articulation values. The opposite happens for high articulation values: the sound starts with its highest frequencies and lower frequencies come in later, with the harmonics filling in from right to left on the final spectrum.

However, this change in frequency is not a straight line. This is because the human perception of frequency is similarly not linear. Humans are better at distinguishes small differences in frequency in low frequency ranges. For higher frequencies, there needs to be a much greater difference in frequency for humans to notice it. Thus the articulation curve is accordingly exponential.

Numerous studies have shown that people can easily tell the difference between a real instrument and a synthesized instrument if the fake sound has all of it's harmonics change in the same way. In other words, to try and sound realistic, this kind of articulation where harmonics come in at different times is necessary. One example is in brass instruments which features an articulation similar to the "BWAA" sound of low articulation values. Once again however, the articulation of the timbre explorer is a compromised design that tries to accomodate a consistent progression over a system capable of mimicing all possibilities. With all the variables involved in articulation (time, amplitude, frequency), there are much more complex articulation patterns out there. For example, sustain variations such as vibrato are not supported in this system.

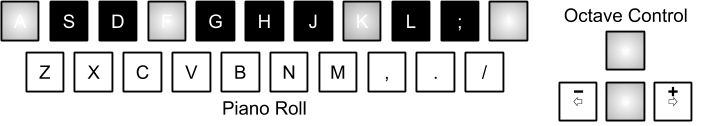

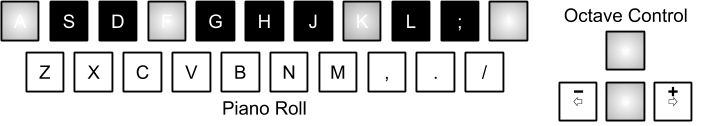

The final dimension is the envelope, which controls how the overall amplitude of the sound changes over time. Perceptually, this dimension is primarily about the onset characteristic of the sound, the way the sound changes at the start. Sounds with a low envelope value have more sudden onsets, as would be heard in percussive sounds like drums, xylophones etc. Sounds with a high envelope value have more gradual onsets, as would be heard in bowed string instruments or wind instruments. From a technical standpoint, the envelope module is modeled by the ADSR paradigm, which stands for Attack, Decay, Sustain, and Release. This divides the sound into 4 consecutive periods of time. To help visualize this, see the envelope graph, which graphs the sound's amplitude over time.

The attack is the first section of the envelope, and represents the time it takes for the sound to reach it's maximum amplitude from the moment it's first triggered. After the attack, the decay refers to the time it takes for the sound to drop to its sustain level, the 3rd section. In the sustain, as the name implies, the sound sustains a constant amplitude for as long as the key is depressed. Finally, once the key is released, the sound goes into the release phase, with the release time referring to the amount of time it takes for the sound to drop from sustain to 0. Generally speaking, the attack time gets shorter as the envelope value decreases, giving us our more percussive sound. As the envelope increases, the attack time increases The decay time has the opposite behavior, increasing with lower envelope values and decreasing with higher envelope values. Upon reaching the furthest reaches of the envelope range, the attack and decay reach maximum or minimum values, and the release time begins to increase the further from the center you are.

Both the envelope and the articulation affect how the sound changes over time. The distinction is that the envelope is much more straightforward, directly changing the overall amplitude of the whole sound, for all of its frequencies. Articulation has a different effect for different frequency components.

The ADSR is a very common tool used to model instrument amplitude envelopes. But while effective, it of course has its limitations. And especially within the timbre explorer system, where all 4 parameters are controlled by a single value.